Activism runs deep in my soul. I moved to Colorado 20 years ago, an idealistic college student searching for community. I found a meaningful opportunity to make a difference as a cannabis advocate when I first built a hemp food company as a 20-something entrepreneur and publicly advocated for marijuana and hemp law reform.

The state’s progression from voter-approved medical marijuana in 2000 to voter-approved recreational marijuana a decade later happened in large part because of concerted efforts from dedicated citizens working together, and it has been gratifying to take part. The yearly gatherings around 4/20 and their history as events of civil disobedience always make me think of my early involvement in cannabis advocacy.

Related: Here’s how Jeff Sessions has disrupted marijuana legalization with words alone

Over the past 20 years, I have worked as a volunteer and had an occasional gig as a paid canvasser on five political campaigns that changed cannabis laws in Colorado. In 2006, my advocacy led me to participate in a raucous protest on the steps of the state Capitol that I will never forget.

But before I get too far, a little background on the campaigns.

For years, politicians didn’t take marijuana reform seriously. Marijuana was the butt of contemptuous jokes and policy reform was swept aside for lack of political persuasion and motivation. Few representatives would listen, let alone publicly support changing laws prohibiting cannabis. The norm was to be tough on drugs. The political climate was frustrating to me, to say the least. Although public opinion was changing, politicians were not willing to stand with the people without an incentive to listen.

Fortunately, the democratic process in Colorado forced their hand.

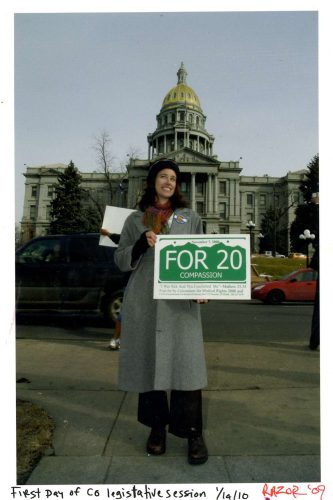

Voters approved Amendment 20, allowing medical marijuana in 2000. The ballot initiative campaign to amend the state constitution had a shoestring budget and a staff of one paid employee and a dozen or so volunteers, most whom were medical patients. It felt like a do-it-yourself campaign. With a partner, I screen-printed a small run of campaign yard signs revamping Colorado’s green mountain license plate with references to Amendment 20 and 4:20. The license plates read: “Vote 4 20” and “For 20.”

Susan Squibb stands near the Denver Capitol in January 2010 with a sign she had made 10 years earlier in support of Amendment 20, a state ballot measure that legalized medical marijuana. (Photo by Todd Razor Arroyo, courtesy of Susan Squibb)

Susan Squibb stands near the Denver Capitol in January 2010 with a sign she had made 10 years earlier in support of Amendment 20, a state ballot measure that legalized medical marijuana. (Photo by Todd Razor Arroyo, courtesy of Susan Squibb)

But our work had just begun.

In 2005, local campaign efforts were organized by Safer Alternative for Enjoyable Recreation, a pilot program of the national advocacy group Marijuana Policy Project. SAFER spread the message that “marijuana is safer than alcohol” and spearheaded local and state ballot initiatives.

That year Denver voters approved Initiated Question 100, which called for city ordinances to be amended to remove all criminal penalties for possession of up to one ounce by adults 21 and older.

In 2006, the statewide Amendment 44, which mirrored the language of the Denver initiative, was rejected by voters.

Then, a marijuana-related 2007 Denver ballot measure also called Initiated Question 100 passed, which led to the creation of a Denver ordinance designating adult marijuana possession as the city’s lowest law enforcement priority.

In 2012, one of the state’s most well-known ballot initiative campaigns, led by a coalition of policy and nonprofit groups, was history-making Amendment 64, which opened the door for a regulated cannabis sales for adults 21 and over and legalized limited possession and home cultivation.

In 2011, Susan Squibb visited the offices of Colorado lawmakers at the state Capitol to distribute a book titled “Marijuana Is Safer” as part of the Women’s Marijuana Movement press conference. (Courtesy of Susan Squibb)

In 2011, Susan Squibb visited the offices of Colorado lawmakers at the state Capitol to distribute a book titled “Marijuana Is Safer” as part of the Women’s Marijuana Movement press conference. (Courtesy of Susan Squibb)

Throughout the campaigns, I collected petition signatures at grocery stores, farmers’ markets, street festivals and Red Rocks tail-gate parties. I distributed my yard signs throughout mountain towns, Denver and other Front Range cities. I passed out flyers everywhere I went. I waved campaign signs and banners on busy street intersections and highways during morning and afternoon rush hours. While spending time spreading the word via phone, I talked to voters and left many persuasive answering machine messages. As a canvasser, I knocked on doors in Denver and Boulder neighborhoods, to speak with voters and hand out literature.

Amid all these enlightening experiences, one of the most memorable was a counter-protest to a 2006 news conference during the Amendment 44 campaign.

A week before the election, then-Gov. Bill Owens held a news conference on the steps of the state Capitol, with a lineup of state and local attorneys and law enforcement officials. They were encouraging a “no” vote on Amendment 44 and had prepared statements on the harms and dangers of marijuana to children and society. SAFER organized a counter-protest to disrupt the event, but no one predicted what was to come.

At the beginning of the conference, one heckler set the tone by yelling at the officials, “Start lying now!” We were a small but vocal group of 30 volunteers — we outnumbered the officials and press at least two to one — interrupting the presser, shouting down the officials as they made their remarks.

In his introduction, Gov. Owens criticized the protesters for their slow response time to his prohibitionist comments. Then Park County Sheriff Fred Wegener was jeered at and then booed during his speech. Several more speakers faced the hostile crowd and were peppered with boos. By the time state Attorney General John Suthers (now mayor of Colorado Springs) took the microphone, the crowd was chanting a boisterous call-and-response — “Hey, hey, ho, ho / You say drink, we say no!” — as Suthers recited his lengthy statement.

I was shouting between spells of silent shock. The protest chants reached a heightened pitch. Shouting over us into the microphone, Owens declared it a sad day in Colorado and then framed the press conference as a legitimate political debate shut down by rude protesters.

The counter-protest was outrageous and the media coverage was successfully shifted to the protest instead of the prohibitionist message.

My years of political advocacy have instilled in me a sense of patriotism and voter power. I am proud that my efforts and the combined work of many dedicated people led to democratic change involving the state’s marijuana laws.

We the people can do this — just ask all of those who never thought they’d see legalization in their lifetime. This is the beginning of what can be substantial and significant policy changes. And with only eight recreational states out of 50 and new uncertainty about how federal marijuana prohibition will be enforced under the Trump administration, we have a long way to go.

2012 protest: Susan Squibb and Dennis L. Blewitt, a.k.a. “Dr. Gonzo,” went to their alma mater, the University of Colorado at Boulder on April 20, 2012. Squibb holds a bag of Blewitt’s legal “gonzo joints,” — handrolled weed-free cigarettes. This was during the years that CU officials closed the campus’ Norlin Quad on 4/20 in efforts to quash what had become an annual gathering of marijuana enthusiasts. (Courtesy of Susan Squibb)

2012 protest: Susan Squibb and Dennis L. Blewitt, a.k.a. “Dr. Gonzo,” went to their alma mater, the University of Colorado at Boulder on April 20, 2012. Squibb holds a bag of Blewitt’s legal “gonzo joints,” — handrolled weed-free cigarettes. This was during the years that CU officials closed the campus’ Norlin Quad on 4/20 in efforts to quash what had become an annual gathering of marijuana enthusiasts. (Courtesy of Susan Squibb)