Pity poor, politicized hemp: guilty by association due to its cousin, marijuana.

Both hemp and marijuana are varieties of the species Cannabis sativa L. But unlike marijuana, hemp contains only trace amounts of the intoxicating chemical compound tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

Hemp has been an agricultural crop for centuries, was grown in colonial America and had a U.S. revival during World War II.

But domestic production of hemp came to a standstill in the 1970s after marijuana was classified under Schedule I in the federal Controlled Substances Act and a federal permit was required to grow hemp.

But that’s been changing in recent years after the 2014 Farm Bill allowed states to approve limited production of industrial hemp. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, as of August 2016 at least 16 states have legalized industrial hemp production for commercial purposes and 20 states have passed laws allowing hemp research and pilot programs.

Use of hemp as a construction material is also part of the revival, thanks to hemp entrepreneurs who are thinking big — and small.

“The reason I was attracted to industrial hemp to begin with was because … it does have the longer-range potential,” says John Patterson, founder of northern Colorado-based Tiny Hemp Houses, a firm that offers consulting services and workshops for prospective hemp home-builders.

Patterson, 54, has spent most of his professional career as a carpenter, craftsman, woodworker and teacher. He’s also an advocate of sustainable building practices. Five years ago he immersed himself in the particulars of hemp-based construction after meeting with Ireland native Steve Allin of the International Hemp Building Association and learning his system for making and using hempcrete.

A closeup of balls of hempcrete. (Ron Sweetin Photography)

A closeup of balls of hempcrete. (Ron Sweetin Photography)

As the name implies, hempcrete is a concrete-like construction material that uses the woody, inner core of the hemp plant mixed with water and lime, or powdered limestone or chalk. Hempcrete can either be molded into building blocks or, as Patterson prefers, it can be mixed on-site into a slurry and poured into frames in order to create hempcrete walls.

According to the National Hemp Association, hempcrete is not only a durable construction material but is both fire and pest resistant. Patterson also notes that it has a measure of flexibility (unlike concrete), doesn’t emit toxic fumes (like some mainstream construction materials) and is vapor permeable.

“One of its number-one qualities is its ability to breathe,” Patterson notes during a phone interview with The Cannabist.

One of the big problems with conventional home construction, he says, is that “we seal up homes so tightly nowadays, and then we create moisture from our breath and our cooking and things like that. That water sits on the surface of the wall and that’s where the molds and mildews grow. With a hemp-lime system, the house absorbs some of that moisture so it’s less likely you’ll have mold and mildew with the proper (hempcrete) recipe.”

Tiny Hemp Houses founder John Patterson is shown at the site of a workshop with bales of imported hemp material to the right of the structure. (Ron Sweetin Photography)

Tiny Hemp Houses founder John Patterson is shown at the site of a workshop with bales of imported hemp material to the right of the structure. (Ron Sweetin Photography)

Hempcrete is also a great insulator, according to Patterson. He says his walls tend to be a bit thicker than in standard construction but that he ends up with an R-22 insulation rating, or the equivalent of a slightly thinner wall insulated with fiberglass.

Currently all the hemp used by Patterson for his tiny home projects comes from abroad. Hemp industry officials say more than $500 million worth of hemp is currently imported into the U.S. annually due to the federal prohibition on cannabis.

Patterson says he imports the hemp as loose particles, in 30- to 33-pound bags from Europe. One of his tiny homes is usually about 120 to 400 square feet in size (For some perspective, the size of an average hotel room is 325-350 square feet). It takes about two tons, or approximately 125 bags, of hemp to build a tiny hemp house, but you can go full-sized too. A 1,500 square-foot house, or about the size of an average three-bedroom home, requires around 1,000 33-pound bags of hemp.

Patterson says he believes in building small, and works with municipalities and do-it-yourselfers to create these smaller living spaces.

“It’s not for everybody, but some people are looking for smaller,” he says. “It’s less expensive. The younger crowd, they don’t want to be tied to a mortgage and they realize they can live with less space. And if you organize that space better it’s amazing how much you can accomplish in a smaller home.”

Coming up May 12-14, Patterson is hosting one of his tiny hemp house/hempcrete workshops, his sixth so far.

As for the people who take part in his workshops John says it’s an eclectic mix. “We get some young people looking for opportunities in the hemp industry,” he says. “Then there’s people from green building or from traditional building, looking for something a little different. Or just people interested in building a hemp house.”

Workshop attendees pour hempcrete as part of the construction of the hemp house. (Ron Sweetin Photography)

Workshop attendees pour hempcrete as part of the construction of the hemp house. (Ron Sweetin Photography)

Patterson says the hemp house movement and interest in using hempcrete has taken on a lot of momentum over the past three years.

“We kind of started the whole trend here in Colorado, but we’re (now) working with states that have nothing to do with marijuana: North Carolina, Kansas, Nebraska,” he says. “So we do have a national momentum going.”

And that national momentum toward hemp farming and hemp construction could end up having major economic benefits for agricultural parts of the U.S. – as well as the nation’s construction sector.

“Farmers across the nation are looking for alternatives,” says Patterson. “The tobacco industry in the South is going away. They really need the economic development to bring a valid crop back to their farmlands.”

As a crop, hemp is drought resistant, grows rapidly and requires relatively little pesticide or herbicide treatment. Industrial hemp, meanwhile, has an astonishing number of uses: from food to fuel to construction materials and clothing.

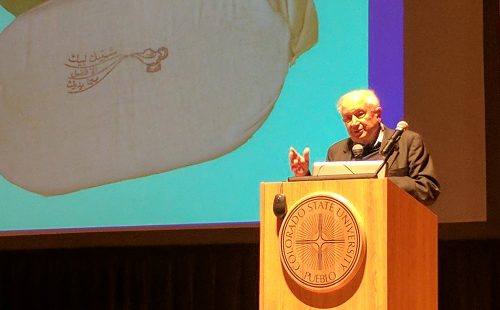

Raphael Mechoulam, a Hebrew University professor and organic chemist with six decades of research on cannabis, was in Colorado to serve as the keynote speaker for the inaugural conference of the Colorado State University-Pueblo’s Institute of Cannabis Research. (Alicia Wallace, The Cannabist)

Raphael Mechoulam, a Hebrew University professor and organic chemist with six decades of research on cannabis, was in Colorado to serve as the keynote speaker for the inaugural conference of the Colorado State University-Pueblo’s Institute of Cannabis Research. (Alicia Wallace, The Cannabist)